Essay #2: Synaptic Jumps / Quantum Leaps?

“Our Time is a time for crossing barriers,

for looking ahead,

for probing around.”

This is one of many deep insights you’ll find on this web site going forward from the man called the Prophet of the Electronic Age, Marshall McLuhan.

McLuhan’s call for “crossing barriers,” on one important level, can be seen as a reference to the opening up the mind by literally crossing from the left-hemisphere of our brain through the anatomical barrier of fibers called the corpus callosum, to the right hemisphere.

While the left hemisphere of our brains, which dominates our educational, social and cultural systems, is wired to break things down into understandable parts and then analyze them to reach a clear conclusion, the right hemisphere is wired for “looking ahead and probing around,” actions more likely to generate imaginative leaps, exhilarating new insights, and new patterns of perception.

McLuhan, who was both revered as the go to media theorist and guru of the electronic age during much of the 1960’s and harshly criticized for uttering cryptic and puzzling phrases, was asked by a TV interviewer why he was so difficult to understand. McLuhan answered, “Because I’m using the right hemisphere when they’re trying to use the left.”

McLuhan pointed out that all new media technologies re-wire the human brain in ways which at first often disrupt and disorientate before generating new gateways of perception (so, it’s not surprising to read so many apoplectic warnings about the dangers of the new gateway to expanded knowledge: The digital screen.)

As McLuhan pointed out in his book “The Gutenberg Galaxy,” the uncomfortable, disorienting rewiring of the brain by new media technology has been going on for millennia:

“If a technology is introduced either from within or from without a culture, and if it gives new stress or ascendancy to one or another of our senses, the ratio among all of our senses is altered. We no longer feel the same, nor do our eyes and ears and other senses remain the same.”

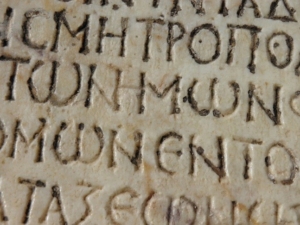

He then notes that Plato, one of the greatest philosophers in human history (in his dialogue, “Phaedrus” around 370 B.C.) made clear his warning about the dangerous new technology of the alphabet and writing. The alphabet and writing dangerous??? Plato was concerned that if people rely on writing instead of memorizing speech, they will too much be dependent on the external written symbols and lose their brain’s ability to “remember of themselves.”

Sounds similar to complaints from educators today that the digital screen is scrambling kids’ brains and students can’t remember what they read as well on the screen as they do from books.

I think we’d all agree that the invention of alphabets and written language was an evolutionary leap in knowledge, despite understandable concerns about how it would rewire the brain going forward. And there’s a delicious irony Plato was well aware of when he wrote about his concerns about the new technology of writing: He was expressing his insights through the medium he was warning against—the written word.

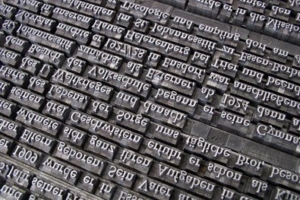

The Gutenberg Leap

Jump cut to the year 1439 as Johannes Gutenberg is unveiling the first print printing press using moveable type. This revolutionary new technology opened up a whole new world, ripping apart the monopolizing grip of the church on both the content and access to knowledge and truth. The printing press transformed science, the economy and communication. At the same time, as had the invention of the alphabet and writing, the new experience of reading books caused severe disorientation and dislocation in the human brain. Many worried at the time that people would isolate themselves, heads buried in books, deteriorating the art of conversation.

Neil Compton in a review of McLuhan for Commentary Magazine in 1965, explained McLuhan’s insight into the limitation of print technology:

“By translating all human experience into the visual, linear, sequential form of written sentences, and by mass-producing the result with the aid of the printing press, Western man has tended to alienate himself from deep involvement with his environment. “Numbed” into a “hypnotic trance” by his visual bias, ‘the bookman of detached private culture’ cannot cope with reality until it is processed into the linear, mechanical order of print.”

This ties beautifully into the need for a shift from left hemisphere dominance to a more right hemisphere thinking. Breaking the world down into understandable, linear, sequential parts is the way the left hemisphere is wired. It demands certainty and resists any attempt to break past its clearly defined territory.

Next Renaissance thinking requires this “crossing the barrier,” moving forward from patterns of perception which served humanity in the past (brilliant technological achievements, but lacking the bigger picture of what technology and its accompanying materialism have wrought (the Industrial Age pollution and now the potentially end game of climate change.

Let’s take a look at how the linear, orderly, sequential process of reading words, lines and sentences in a printed book, while fostering focused readings of interesting subjects on the one hand, limits the associative, synaptic leap powers of the brain on the other.

A good analysis of how our brains work when reading print can be found in the Scientific-American article, “The Reading Brain in the Digital Age” by journalist Ferris Jabr.

One of its main conclusions, and the reason so many educators bemoan the amount of time students spend on digital screens, is because tests show that reading on the printed page is more conducive for “working-memory.” If this sounds like a familiar refrain, earlier I pointed out Plato had the same concern about the invention of the alphabet and written language. It should also be noted that more modern testing has shown that as the years go by and students (as well as most of the rest of us) get experience reading and researching on the digital screen “working-memory “gets better.

But for our purposes, helping to usher in the Next Renaissance, there’s a deeper point here: What’s so great about “working-memory.?” Most of the school curricula currently in use are based on a 19th century industrial model which rewards students for memorizing facts in Pavlovian fashion, regurgitating them back on tests to show they understood what administrators who chose what books would be used wanted them to learn.

The word, “education,” has a very important etymology. It come from the Latin phrase “to draw out,” i.e., to bring out one’s natural curiosities about the world, not to stuff in controllable information, which is still the favored mode of education at least up and through high school.

As the article linked to above points out, there is also a heavy “physicality” involved in reading books along with an unconscious sense of clearly defined boundaries no longer restricted on the digital screen. There is a comfort in reading a book, knowing these boundaries are there. But, also, a limitation, mostly subconscious, indoctrinating the sensibility that life is linear and has clear, definable boundaries. As quantum physics and more recent scientific/philosophical breakthroughs such as Chaos theory, Self-Organization, Flow and Emergent theory reveal, nature, and for the most part, our brains are based on non-linear, unpredictable, synaptic jumps.

Maryanne Wolfe, whose doctorate is in human development and psychology, is quoted in the article:

“In most cases, paper books have more obvious topography than onscreen text. An open paperback presents a reader with two clearly defined domains—the left and right pages—and a total of eight corners with which to orient oneself. A reader can focus on a single page of a paper book without losing sight of the whole text: one can see where the book begins and ends and where one page is in relation to those borders. One can even feel the thickness of the pages read in one hand and pages to be read in the other. Turning the pages of a paper book is like leaving one footprint after another on the trail—there’s a rhythm to it and a visible record of how far one has traveled. All these features not only make text in a paper book easily navigable; they also make it easier to form a coherent mental map of the text.”

But while it’s more comfortable right now for most of us to navigate through the single insights of one author writing in the familiar, measured lines of printed on pages in a book with clear boundaries, the full capacity of thinking is limited when seeing the world in linear, sequential order.

None of this is to imply that books are no longer relevant. The pleasures of reading text will continue to be a significant part of learning. At the same time, the shift to the digital screen offers exponential leaps in exploring and synthesizing information.

The Shift to the Digital Screen

All the way back in 1945, Vannevar Bush, an inventor who worked on some of the early analog computers, anticipated both McLuhan’s insight and the World Wide Web:

“With one item in its grasp, the human brain snaps instantly to the next that is suggested by the association of thoughts, in accordance with some intricate web of trails carried by the cells of the brain”

This insight into the “intricate web of trails carried by cells of the brain” anticipates the connected network of the world wide web and the dynamic “snaps” of hypertext links which break through the limitations of a bounded page of print and open up “trails” of connected thoughts.

(NOTE: Clearly the digital screen is being manipulated by advertisers and fake news snake oil salesmen and there is a serious problem with kids getting addicted to the screen. While these problems need to be addressed, as previously noted, EVERY major new media technology “disorients” at the beginning and creates new “downfalls” along with greatly expanded “upsides.” Much of this can be understood through McLuhan’s insight:

“It is the framework which changes with each new technology and not just the picture within the frame.”

Adjusting to an entirely new media “framework” jolts the mind on both the unconscious and conscious levels, but, as history as shown, after initial disorientation and warnings, the new media leap us forward on our evolutionary trip.)

Another important point often ignored or forgotten by those admonishing the hyper speed/hypertext disorientation of the digital screen is how this new media technology, as with those before it, is expanding knowledge exponentially.

Writer and teacher Melissa Gouty, who clearly loves books and literature, nonetheless understands the economic and environmental advantages of the digital screen:

“The cost of digital books is less than printed books, allowing schools and libraries to purchase more, new inventory at a fraction of the cost. Readers can access online materials through free sites, giving them resources that would not have been available if they have had to pay for print books.

Digital resources don’t require physical space. No one has to build additional wings, construct shelves or figure out where to house collections. Online materials are not subject to mold, mildew, or theft like print books are.

Online materials are accessible at any time of the day or night, and deliverable within seconds. They are portable and without weight.”

The New “Biliterate Brain”

The analogy which comes to my mind regarding the relationship of the digital screen to the printed page is that of Einstein’s revolutionary theory of relativity to Newton’s laws of cause and effect. Einstein didn’t prove Newton wrong. In fact, today Isaac Newton is still considered one of the greatest scientists of all time and his insights into the physical world remain highly relevant. But Einstein did prove Newton’s insights to be limited. At speeds nearing the speed of light, new ways of looking at the world were needed in order to make the leap forward into the quantum age.

To use a phrase now becoming more popular, we need to become “biliterate,” that is, learn to use the distinct advantages of both the printed page and the digital screen while understanding they each wire our brains differently.

Melissa Gouty, addresses this in her article “Why You Need to Develop a Biliterate Brain—And How to Do It.” She writes:

“We live in a modern world where we daily navigate the vast network of digital sources. But we also have to be able to feel, understand and enjoy the depth of literature…

We NEED biliterate brains capable of both FAST and SLOW styles, looping and linear patterns to survive.

Digitally-developed brains are capable of flipping through visuals, assimilating ideas, jumping from thought to thought, and finding information FAST. Print-oriented brains allow us to SLOW DOWN, savor the language, and consider the implications of the words on our lives.”

CODA

We have left the world of one step at a time, linear, sequential thinking.

While continuing to experience the joys of sitting down with a good book and the need for slowing our brain waves down into contemplative insight, we are being pushed forward by the inevitable force of evolution into the sped up, hypertext, digital zeitgeist of the synaptic jump and quantum leap.

McLuhan anticipated this back in the 1960’s when he stated,

“After three thousand years of explosion, by means of fragmentary and mechanical technologies, the Western world is imploding”

What’s called for to deal with systematic breakdown of economic, social and political systems is a deep psychological paradigm shift in emphasis from the left-hemisphere focused point of view to a more right-hemisphere openness to probe novel, expansive regions of the human brain, to detect the rays of light which inevitably shine through the cracks of the systematic breakdown.

In the emergent Digital Age, with our brains extended outwards through the World Wide Web, we are adapting to a less fixed/linear/sequential reality to one allowing for a remixing of previous patterns of thought and more innovative, imaginative patterns of perception. Disorienting, no doubt. Frightening, if we stay controlled by our brain’s amygdala and restricted to the more certain, predictable confines of the left hemisphere. As McLuhan made clear, this is a time “for crossing barriers, for looking ahead, for probing around.”

He also offered a therapeutic insight regarding the chaos, confusion and anxiety that accompanies the re-wiring of the brain through the invention of powerful new media technology such as the World Wide Web:

“Our Age of Anxiety is, in great part, the result of trying to do today’s job with yesterday’s tools and yesterday’s concepts.”

And

“There is absolutely no inevitability as long as there is a willingness to contemplate what is happening.”

End.

Enjoy the quotes and links below:

“My thesis is that for us as human beings there are two fundamentally opposed realities, two different modes of experience; that each is of ultimate importance in bringing about the recognizably human world; and that their difference is rooted in the bi-hemispheric structure of the brain. It follows that the hemispheres need to co-operate, but I believe they are in fact involved in a sort of power struggle, and that this explains many aspects of contemporary Western culture.”

Psychiatrist, Neurolgy Researcher, author, Dr. Iain McGilchrist

.

“Traditional education gives little room for students to develop their creativity and outside-of-the-box thinking beyond predetermined, standardized boundaries. The next generation needs to be prepared to tackle not only the known, but also the unknown problems our world will face. Therefore, we must be forward thinking about how we train and inspire our upcoming generation…focusing more strongly on developing right-hemisphere potential, and corresponding values like intuition, creativity and empathy, is essential.”

Article about author Daniel Pink