Essay #4: Where is Evolution Pointing its Finger?

In the mission statement for this website I write:

“Here in the 21st century, with exponentially expanding computer intelligence and worldwide digital connection as the driving forces, evolution is accelerating at a speed never before experienced in human history…

We have left the world of logical, linear, one step at a time, sequential thought,

We have entered the age of the quantum leap.”

Two scenes from one of the greatest films to portray a quantum leap in consciousness set the stage for today’s essay.

2001: A Space Odyssey was purposely designed to provoke, disorient and challenge. In this essay let’s look at the film as powerful metaphor for the required shift in emphasis from the left hemisphere of the viewer’s brain to the right hemisphere.

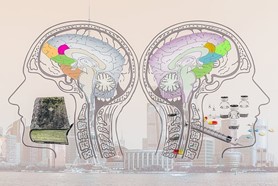

As previously discussed, our brains are divided into a left and right hemisphere. They are separated by a bundle of nerve fibers called the corpus callosum through which the two hemispheres can communicate with each other. The key to understanding their relationship, as masterfully explicated in Iain McGilchrist’s book, The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World, they each see the world from very different perspectives

The left hemisphere sees a material world which can be understood best by breaking things down into parts and figuring out how they fit together. Very useful for creating advanced technology and organizing large systems. But its weakness is a constant search for certainty–it’s not comfortable with complex questions which require a tolerance for ambiguity and novelty. It also has a tendency to get stuck within its own boundary.

The right hemisphere, which is physically larger and has more synaptic connections, seeks a “bigger picture” of the world and our place in it. It’s capable of making intuitive, unpredictable leaps into new ways of perceiving and understanding.

As Iain McGilchrist writes,

“While making it clear that both the left and right hemisphere’s ways of looking at the world are important, “…I suggest that it is as if the left hemisphere, which creates a sort-of self-reflexive virtual world, has blocked off the available exits, the ways out of the hall of mirrors, into a reality which the right hemisphere could enable us to understand.” This has resulted the modern society, both physically, emotionally and spiritually becoming “increasingly mechanistic, fragmented decontextualized world, marked by unwarranted optimism mixed with paranoia and a feeling of emptiness….reflecting, I believe, the unopposed action of a dysfunctional left hemisphere.”

2001: A Space Odyssey can be seen as a virtual celebration of the imaginative leap capabilities of the right hemisphere. Here is director/co-author Stanley Kubrick’s own description of the film in an interview with Eric Norden for Playboy Magazine:

“2001 is a nonverbal experience; out of two hours and 19 minutes of film, there are only a little less than 40 minutes of dialog. I tried to create a visual experience, one that bypasses verbalized pigeonholing and directly penetrates the subconscious with an emotional and philosophic content. To convolute [Marshall] McLuhan, in 2001 the message is the medium. I intended the film to be an intensely subjective experience that reaches the viewer at an inner level of consciousness, just as music does; to “explain” a Beethoven symphony would be to emasculate it by erecting an artificial barrier between conception and appreciation. You’re free to speculate as you wish about the philosophical and allegorical meaning of the film — and such speculation is one indication that it has succeeded in gripping the audience at a deep level.”

Note words and phrases Kubrick uses such as:

- “nonverbal” (psychologists have shown that most communication between and among us is at the nonverbal, subconscious level, a region the “implicit” right hemisphere is more comfortable in than the “explicit” left which depends much more on written and spoken verbal language;

- “free to speculate,” again a nod to the “implicit” where the right hemisphere subjectively fills in the gaps rather than the left hemisphere’s preference for exactness and objective clarity;

The Jump Cut / Synaptic Leap

One of the most unexpected, brilliant “jump-cut” edits in movie history is the rotating bone flung into the air by one of the prehistoric apes morphing into a futuristic space shuttle heading towards the moon.

The bone reflects the leap in intelligence of the leader of one of the ape groups after he and other group members flail nervously around the strange monolith (which helps induce the synaptic jump in the lead ape’s brain). This ape discovers for the first time that the bone can be both a useful tool for digging and a powerful weapon for beating off other ape groups competing for territory around a life-supporting source of water.

The jump-cut edit to the modern space shuttle, from one point of view (the left hemisphere) is an exponential leap forward…who can deny the leap in tool sophistication between a primitive bone and a space shuttle to the moon? From a technological perspective, yes. But is it an equally large leap in consciousness?

We get the answer when we witness the lead American scientist, Dr. Heywood Floyd, under military orders, refusing to reveal to Russian scientific colleagues he has previously worked with any information about the discovery of another monolith found by American scientists doing research on the moon. Rather than share the information in a collaborative effort, the American response is to keep the discovery secret, cutting off all communication from American scientists on the moon. Floyd’s body language and verbal language is incredibly stilted, emotionally void, tight-lipped, protective.

At the conference on the moon with fellow scientists, Floyd makes clear the need for absolute secrecy: If word got out that an artifact had been found buried by an alien intelligence, it was assumed people on earth would freak out. How different is it from the primitive ape’s use of the bone to prevent other groups from using the water hole on the African savanna different from lead scientist Floyd preventing any other nation, or for that matter, the inhabitants of earth, from any information about the monolith? Both moves come from the part of the brain which is dominated by a strict territorial imperative. With the prehistoric apes, it was the need to dominate the water hole against any outside group–with the human scientists on the moon, it was the need to conform to strict, bureaucratic protection of the existence of a higher intelligence.

So, one conclusion taken from this is that while we homo sapiens have figured out how to make huge advances in the usefulness of tools/technology, a primary attribute of the left hemisphere of the brain, there is not nearly the leap in consciousness that understands the advantages of collaboration and openness to the new and unpredictable–that which requires a leap in understanding, attributes more conducive to the right hemisphere.

Unplugging HAL

One of the most crucial, intriguing questions about the film has been “What made HAL go crazy?” After making a computational error, the two astronauts are convinced the super computer, responsible for all the complex mechanisms of the space craft, needs to be shut down. HAL, unknown to the two astronauts Bowman and Poole who made sure the computer couldn’t hear their plan to shut him down, can, however read their lips. Out of self-protection (and to his computer brain, out of his instructions to guide the spacecraft to its intended destination, it murders one and refuses to let the other, Bowman, re-enter the spacecraft.

What caused HAL to break down and become a murderer? According to Kubrick, in an interview with author, journalist Joseph Gelmis: “In the specific case of HAL, he had an acute emotional crisis because he could not accept evidence of his own fallibility.”

But I prefer the explanation given by Arthur C. Clarke, who co-wrote the screenplay with Kubrick, then gave his explanation in his sequel novel 2010: The Year We Make Contact, (also made into a movie.) Clarke, who had a background as an engineer/science writer as well as science fiction novelist, explains in the novel sequel that HAL broke down due an inability to resolve two conflicting algorithms inputted by orders of the humans in charge of the Jupiter mission. On the one hand, HAL was instructed to give astronauts Bowman and Poole accurate information to ensure the spaceship gets to Jupiter. At the same time, those in charge of the mission feared that if the astronauts knew they were heading towards an alien intelligence, they’d freak out and not be willing to complete the mission. So, HAL, after being instructed to give Bowman and Poole accurate information, was given the contradictory instruction to lie to them about the true purpose of the mission.

This breakdown in HAL’s brain when trying to hold two opposing algorithmic instructions is analogous to the human phenomenon we’ve all experienced in our brains: cognitive dissonance. This is the psychological pressure felt when holding two or more contradictory thoughts, values or beliefs at the same time. Doing this while accessing the right hemisphere of the human brain’s capacity to use ambiguity and volatility to reach a higher level of understanding can actually lead to a more enlightened vision as will be noted towards the end of this essay. And as awesome as the leap in AI has been since the turn of the new century, computers can still not match the attributes of the human right brain hemisphere.

So, in 2001: A Space Odyssey, according to Arthur C. Clarke, HAL pretends to make a potentially disastrous mistake regarding one of the spaceship’s mechanisms so that when the two astronauts left the spaceship to fix the exterior unit, HAL could cause their deaths and would no longer have to maintain the lie. Bottom line: It was the human error of inputting two contradictory instructions that fractured HAL’s computer brain.

A Metaphorical View

On the literal plot line level, HAL needed to be turned off since he had become a murderer. But we can also consider the unplugging of HAL’s brain as reflecting astronaut Bowman’s need to cross over the Corpus callosum of his brain from predominantly left hemisphere (organized, focused, analytical, more predictable) to his right hemisphere (expansive, curious, more open to totally novel perceptions and sensations).

The left hemisphere of Bowman’s (or any human’s) brain could not tolerate Bowman’s mind-altering, totally mind-altering trip through the Star Gate set up by the monolith, which appears orbiting Jupiter right before the bizarre trip begins.

But before looking at Bowman entering the Star Gate:

It’s important to acknowledge the crucial value of the left-hemisphere in the big picture view of the Jupiter mission. Without the ordered, sequential, organized mind-set of the two astronauts working with HAL, the exponentially superior brain at maintaining the mechanical quality of the spaceship, Bowman would never have reached the Star Gate.

At the same time, without moving from the left hemisphere mode to right hemisphere (the Star Gate seen as a metaphor for the Corpus callosum, Bowman’s brain would have likely shut down, unable to deal with the disorienting, massive evolutionary leap in consciousness his mind experiences (a supersized version of cognitive dissonance).

Entering the STAR GATE

At one metaphoric level, the unplugging of the computer/left hemisphere and the crossing over to the right hemisphere Stargate begins an accelerated evolutionary leap towards a newborn star child, a re-birth of Bowman (in human history a rebirth is represented by a Renaissance, “from Old French renaissance, literally “rebirth,” usually in a spiritual sense.”

When asked to talk about the final scenes, Kubrick responded, “No, I don’t mind discussing it, on the lowest level, that is, straightforward explanation of the plot:”

“When the surviving astronaut, Bowman, ultimately reaches Jupiter, this artifact sweeps him into a force field or Star Gate that hurls him on a journey through inner and outer space and finally transports him to another part of the galaxy, where he’s placed in a human zoo approximating a hospital terrestrial environment drawn out of his own dreams and imagination.”

We are now in the region of “dreams” and “imagination,” the province of the right hemisphere (Neurologically in our brains, Dr. Iain McGilchrist writes “…during REM sleep and dreaming there is greatly increased blood flow in the right hemisphere…EEG coherence data also point to the predominance of the right hemisphere in dreaming.”

Kubrick continues explaining the story line of the final Star Gate scenes:

“In a timeless state, his (Bowman’s) life passes from middle age to senescence to death. He is reborn, an enhanced being, a star child…and returns to earth prepared for the next leap forward of man’s evolutionary destiny.”

It is the premise of this website and the webinar associated with it that we are on the precipice of an evolutionary leap…a leap induced by exponentially expanding computer intelligence, the fast approaching scientific breakthroughs in genetic engineering and brain implants along with the potential for unprecedented breakthroughs in philosophical wisdom and psychological expansion through the collaborative network of the World Wide Web.

2001: A Space Odyssey, despite being produced over 50 years ago, remains one of the most powerful symbolic experiences of this potential for ‘evolutionary leap’ premise and, central to our theme here, remains one of the most effective symbolic celebrations of the crossing of the corpus callosum from the predominantly technical, specialized, utilitarian, closely focused left hemisphere to the more big-picture, imaginative, empathic, paradigm-breakthrough qualities of the right hemisphere.

CODA

We are the first beings on the evolutionary path here on planet Earth with the ability to consciously direct our own evolutionary path.

So, in what direction are we being pointed? The insight from one of the most insightful historians on the planet right now, Yuval Noah Havarti, which we highlight on the home page of this website is a deep insight into the speed of change generated by expanded computer intelligence percolating through all aspects of our lives:

“In long run, people will have to continually reinvent themselves.”

What if we combine that insight with one from the mind of Marshall McLuhan, the provocative media theorist we quote often on this website?

“We Shape Our Tools,

And Thereafter Our Tools Shape Us”

2001: A Space Odyssey points to both the crucial importance of computer intelligence and its ultimate failure without the overriding influence of the right hemisphere of the human brain.

It is quite a challenge to feel what astronaut Bowman must have been going through in his mind after entering the Star Gate and experiencing those strange, unprecedented transitions leading to his rising from his death bed, pointing at the monolith which appears close by.

In nature, here on planet Earth Bowman’s leap is perhaps best reflected in the astounding molecular transformation from caterpillar to butterfly. In human terms, spiritual teachers throughout the flow of the Perennial Philosophy, speak to the necessary inner transformation within the psyche in order to reach a deeper perception of reality.

Reflecting on the dry, impersonal, tight-lipped, overly defensive scientists and engineers who populate 2001: A Space Odyssey and the over-dependence of the left hemisphere limited world view which has brought our civilization to the precipice of systematic collapse (climate change) , I again point to an insight from Iain McGilchrist:

“When we remember that it is the right hemisphere that succeeds in bringing us in touch with whatever is new by an attitude of receptive openness to what is—by contrast with the left hemisphere’s view that it makes new thing actively, by willfully putting them together bit by bit—it seems that here, too, is evidence, if any further were needed, that the right hemisphere is more true to the nature of things.”

The left hemisphere of the human brain is great at inventing new tools and technology; the right hemisphere more suited for re-inventing our perception of the world, particularly relevant when the “nature of things” feels like they are shifting dramatically under our feet.

2001: A Space Odyssey is a visually beautiful cinematic trip leading to the “re-birth” (Renaissance) guided by an alien intelligence.

The question: Here on planet Earth in the year 2021, is the “nature of things,” the pull of evolution, pointing us on a trip towards a synaptic leap within the right hemisphere of our brains, to “re-invent” the way we perceive ourselves and our place in the world?

END.